Secrets of the Launch License: Part 1

Taking the Easiest Path for OCST Would Have Cheated The Future Industry. The easiest way to illustrate the difficulties there were in designing OCST’s licensing process is to ask readers to imagine that in 1984 there were 100 parallel universes to ours, each with its own identical Earth. On each of these Earths, a different group of people was developing the commercial launch licensing process; there would be 100 different license designs as a result.

In most of those parallel worlds the license would have been designed with the title “expendable launch vehicle license”, and whenever the launch vehicle was mentioned in the OCST regulations, it would have been referred to as the “expendable launch vehicle”. At the time, virtually all the vehicles were expendable. If you talked to McDonnell Douglas, Martin Marietta or General Dynamics in those days, they would have laughed at the thought of a commercial reusable or manned vehicle. McDonnell Douglas had designed a reusable prototype, but after it crashed, their program disappeared. There were the entrepreneurs, of course, that talked about different concepts, but at that time, the “real” space veterans (i.e. NASA and Air Force types) simply dismissed those ideas. I had many government experts telling me that there was going to be no successful private sector because the private sector could not afford the cost of getting into the space game.

Most parallel world licenses would also have been focused on the government launch ranges. In those worlds, OCST would not have felt it was in a race to conduct the research necessary to evaluate novel or complex launch activities. In fact, at that time, we were told that there was nothing for OCST to do with this new responsibility. If a company was going to use a government range, all we had to do is give the company a piece of paper that said, “License”. The reason was that then further action was required. In fact, that is what NASA and the USAF expected us to do. The government took care of everything. Most people at the time just assumed that all launches would take place from government launch facilities. After all, the Atlas, Delta, and Titan weren’t going anywhere. All the other companies were small-time stuff, as far as the experts were concerned, and they really weren’t going to amount to much.

In many of those parallel worlds, DOT would not have become lead agency because the Department would have stuck with its choice of putting the responsibility in FAA and, therefore, the Department of Commerce would have been selected instead. In other parallel worlds, the State Department wouldn’t have agreed to transfer the “export launch license” to DOT, nor would it have endorsed the idea that legislation was needed; hence in those worlds, the Commercial Space Launch Act would have had to wait. In others, alternatives to NASA and the USAF insurance practices would not have been proposed because they were the space experts not to be challenged, and some other solution to the insurance industry’s concerns would have had to have been found. Success in this period in time came from strategies that went counter to the prevailing trend.

Would the Bezos, Musks, and Rutans of the world still have attempted to pursue their dreams in each of the 100 parallel worlds? Quite possibly not–especially those worlds where the regulatory process placed an emphasis on the status quo. Unless someone makes a film like “It’s a Wonderful World” about space, it’s difficult to know for certain how things would have looked. However, my guess is that Bezos, Musk, and Rutan wouldn’t have gone about it in the same way because the process would have been more difficult. (See the post on Burt Rutan in another section of this website and we can wonder whether Burt Rutan would have gotten into space at all if he had not come to DC.) And certainly, the plethora of spaceports that exist today, would not be conceivable under a regimen that essentially steered launch companies into government launch ranges. Regulations subtly mold behaviors without the subjects being aware that they are being molded.

The question also could be asked whether today’s OCST regulations keep the spirit of our original regulatory policy, or have they been influenced by the FAA behemoth of which they are a part? Are today’s regulations shaping the future direction of the industry, or are they designed in such a manner that the industry is able to steer toward optimal advancement and at a pace as fast as it wants? Are the regulations today encouraging industry to utilize the most innovative approaches to safety by taking advantage of rapidly evolving technology, or are they encouraging an old-fashioned government launch range approach to safety? Are the regulations today taking a balanced approach to risk recognizing that space launches today are still so infrequent that the aggregate risk to the public is relatively minimal, or approaching risk in the same manner as FAA approaches air carrier safety? Is the standard of risk comparable to what is accepted across the breadth of transportation industries, or is it reaching the point of being risk-averse as when NASA and the US Air Force set their insurance requirements in 1984; or is it being held to the standard that Tony Broderick, the former FAA Associate Administrator, told me he was going to use just before DOT briefly lost the lead agency role to Commerce. Today’s industry is much better able to answer that than the industry we saw in 1984.

Features of the Launch License: Modular, Modular, Modular!!!!

Development of the launch license design was difficult because we had to consider the second and third order consequences of each option in the launch license process. The license design had to be able to handle manned vehicles as easily as it processed ELV launches so that our mentality was open to any and every imaginable concept.

The license had to be modular—in fact, extremely modular. Tying everything into one big process only meant that everything had to proceed in sequence. However, real life doesn’t proceed in sequence. The license had to be so modular that it was possible to get “B” approved before “A”, and “D” before any of them.

Payload operators needed to know whether the government would approve their product before they could market their product or plan to purchase a launch. Companies with creative space applications (i.e. payloads) that fell under our licensing authority had to be able to get an early approval without a launch vehicle, so they could sell enough “product” so as to have the funding to purchase a launch.

Launch companies needed to know if the safety approach they planned to use in lieu of going to a government range was viable before they could decide whether to go to a new location. The state of Hawaii had to know whether the location of a proposed launch site was viable and whether it would pass the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) before it could fully invest in its concept. Investors don’t like to put their money into speculative ventures that the government might simply kill tomorrow. If space was to truly have a wide open sector for commercial development, there had to be a mechanism for virtually any entrepreneur who could play a key role in that critical commercial loop (e.g. launch site, or vehicle, or vehicle concept, or payload) to get an answer without the other components being present.

Features of the Launch License: Simplicity!!!!

Our license had to entertain the idea that virtually anything was possible for the industry to bring to our door. They only had to prove that they could keep their concept safe to the public. Their means didn’t have to be complicated. That meant that we had to reduce the approval process to the most basic components of safety. When we did that we found that space vehicles were only as different from other forms of transportation, as each form was different from another. For example, almost everything would have to be tracked whether, by eye, radar, inertial guidance computer or GPS; everything would have some way to turn off or stop a moving object, whether through a self-destruct device, power cut-off, or by steering; everything would have someone or something in the loop that was responsible for safety, whether it was a safety officer, driver, pilot, or computer. This was something many of the “safety experts” of that day did not understand. They had bought into the conventional space safety wisdom they were taught; to them, space was far different, more dangerous, and complex than anything else. When we found the very first space safety pioneers, we discovered they thought like we did.

Features of the Launch License: Pre-application Consultation!!!

We quickly realized that if one wanted to be quick when an applicant presented a request, then it was important that the party be able to come in advance of the application. The Commercial Space Licensing Act (CSLA) gave us 180 days to approve an application, or we would notify the applicant within 120 days that we would go past that deadline. We also suspected some were going to apply with fewer than 180 days to launch. Talking before the application could give us early warnings about issues, or provide useful guidance to the applicant. We couldn’t prejudge an idea, but we could talk through the concepts and identify the issues that might become important later. An example is when Deke Slayton came in to discuss cremains. He and I had a wide-ranging discussion. Part of it centered on orbital debris, which at the time was just beginning to be understood. The concept of using space as a graveyard was novel enough, but our conversation migrated to a topic that SSI had not thought about, and which probably would have been used by NASA or DOD to recommend against approving cremains. However, as a result of that discussion, SSI’s application fully addressed the debris issue and was approved.

The Way it Was In 1984

The design of the launch license created in response to the Commercial Space Launch Act was not perfect: it was far from that. It was new and untested. Only time could provide the experience to improve the licensing process. However, it was designed with the most contemporary regulatory thought at the time, and in the spirit of Executive Orders 12291 and 12498. These EO’s articulated the need for government regulatory agencies to use no more than the lightest regulatory touch necessary to accomplish the objective. It was designed to allow any and all space launch technologies and companies to come our way without fear that their approach would be ruled out. It was designed so that if at any time the regulatory process was too burdensome, the burden could be lifted without changing the rules. And it was designed so that if in the future the Office wanted to make them more complex, it would take a conscious effort and specific intent to do so.

The problem with the word “license” is that it means so many different things to different people. On the one hand, it can be something simple, such as in “driver’s license” or hunting license. Or it can be something incredibly complex, like for a nuclear power plant. Most participants in an industry that had only taken direct orders from the US Government, and which had never been regulated, didn’t know the difference. OCST did.

A launch license process that said, “Do your launch at the government launch ranges and follow their instructions, and that is all you have to do”, would be like a drivers license. In the case of the driver’s license, it’s relatively easy to obtain because there are many rules and regulations that have been created over time, and all a person needs to do to get their license is show they know how to operate the vehicle and prove they know the key rules by taking a test. This is a design regulation system and leaves little room for innovation.

A launch license could, alternatively, say, “You don’t have to do it the way government launch ranges do it, or you can propose to change the way they do it. You just have to show and prove to us how that would work”. These are performance regulations. The challenge is making sure the companies provide enough of a written record to demonstrate that they know how to make their activity safe and that they have included enough “procedure” in their applications that they can be required to follow their procedures. The “license” in this instance, often itself becomes the regulation that the company follows. The advantage to this approach is that no two companies have to have the same approach or technologies. Most importantly, innovators have a path to success without having to ask for a “waiver”, “exception”, or seek an alternative rulemaking.

The OCST license for launches took the “performance standard” approach, although there was a “shortcut” if a company wanted to use a government range and contract with the range for safety. There were no pre-existing standards. Had the process existed when SSI first launched in 1982, it could have secured an approval to launch with far less effort and in much less time. For Starstruck, the new license process would have taken 25% of the time it took to get its “export launch license”. The license was designed to accommodate virtually every type of technology. It was designed with the future in mind, although no one knew what the future would look like at the time of design. Based on what we are seeing emerge today in the form of launch vehicles, it was designed the way the “future” needed it to be.

People looking at the license today might simply assume that the license is straightforward and common sense. Some might even think “that is was the only way to design it.” Others might think that it didn’t take much time to come up with this concept. “Au contraire, mon ami!”

Features of the Launch License: A New Role for the Government Ranges!!

In early 1989, the Office of Commercial Space Transportation provided launch companies a document entitled “Information To Be Included In the DOT/OCST Commercial Launch License Applications” (dated effective 3/89). This document provided augmented information requested in OCST’s regulations, and it reaffirmed a radical concept articulated in OCST’s regulations. As the very first precept the instructions stated:

“The company has sole final responsibility for the public safety. Its ability and resources to handle this responsibility must be documented. The applicant can use contractors (which could be launch range personnel)…”

Later, the instructions for the Safety Review open with this direction:

“In contrast to the Mission Review which addresses policy issues, the Safety Review is devoted to the applicant’s operational capabilities to protect public safety. The launch services company applying for the license must recognize that it, and not its contractors (including the launch range) is ultimately responsible for public safety”.

The purpose of this construct was to change the prevailing paradigm in which the large launch companies existed. Companies using the government ranges were accustomed to being told what to do because they were former government contractors. These companies were accustomed to blindly doing anything the range safety personnel directed them to do. Cost didn’t matter because, as government contractors, all the costs of compliance were covered by either NASA or the military, depending on who was contracting for their launch vehicle.

If the companies were truly to mature and become firms capable of operating anywhere, even not at a federal launch range, they had to know that they were the launch operators and that they were responsible for safety, not the government launch officials. Thus, the regulations put them in charge of safety. It would not matter that they might go to a government launch range and be told they had no choice about how the safety would work. The fact was that the government people were now contractors to the commercial space companies, and should a government person do or order something unsafe, it was the companies’ responsibility to correct that.

Shortly before we issued the final regulations, we held a symposium at Cape Canaveral to brief all the launch companies and interested parties about how the licensing process was going to work, including the roles and responsibilities of commercial space companies and the government ranges. The day before that presentation, I was told by the USAF that a panel of 4 or 5 AF generals wanted to hear what I was going to tell the industry. I spent a very long afternoon in front of this panel describing the licensing process, and answering questions. I think we spent more time talking about this curious role reversal of US Government turned contractor. In the end, they accepted the concept, and I briefed the industry the next day.

Feature of the Launch License: Streamlined Coordination with NASA and the USAF

The Commercial Space Launch Act included a feature that DOT coordinate licensing actions with NASA and DOD. At the time, there were three major possible explanations for this Congressional requirement: a) Congress was concerned about a nefarious use of space—after all, commercial activities were not envisioned under the various outer space treaties; b) Congress was concerned DOT needed technical expertise; or c) NASA and Air Force didn’t trust a third party in the space arena and got that language added so they had a check on the new kid on the block.

It was a curious requirement because the DOT regulatory role was to ensure public safety and, typically, that is a technically focused issue. None of DOT’s other safety agencies, such as the Federal Aviation Administration, US Coast Guard, Federal Railroad Administration or any other DOT agency, automatically coordinated their regulatory actions with other agencies. However, they did when it seemed like there was a good reason.

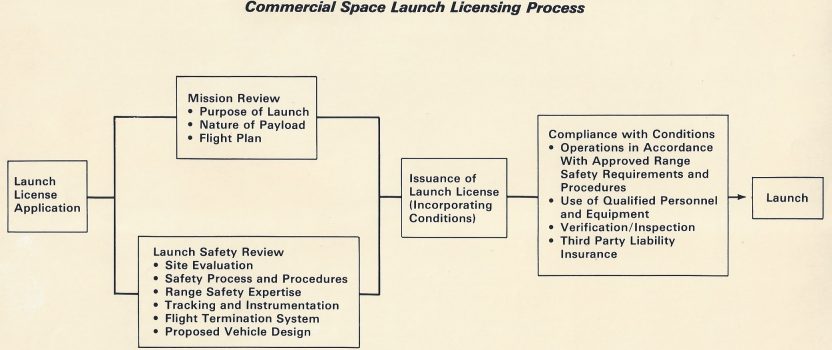

The US court system typically defers to agency interpretations of their respective enabling legislation, so we interpreted the Act to mean that we coordinated when it made sense. Having been involved in studying or solving the morass of government agency coordinations needed for SSI and Starstruck, I knew that blindly following a dictate to coordinate could be detrimental to the industry. We didn’t need NASA or USAF input on whether a launch was safe. But we could use their support to know whether a launch affected their operations in space, or if there was some aspect about a payload that impacted national interests. This is one of the reasons the license review was divided into two parts; it eliminated the confusion about when NASA and the US Air Force would be involved. Their roles would be in the “mission review”. Even then, their involvement would be finely delineated so as not to include their opinions about the proper use of space, or things that might compete with their own projects. Remember, this was an era of changing roles: two major space monopolies in the form of NASA and the USAF were suddenly encountering a new, intrusive party in the space game. The rules that these two Agencies had worked out between themselves were not the rules the new players would play by. OCST’s role was to make sure our regulatory process did not give the two former monopolies the means to curb or influence this emerging industry.

Feature of the Launch License: Don’t Reinvent the Wheel; Let Other Agencies Do Their Jobs

Our authority was pretty broad. We could waive the requirements of other agencies, and, conceivably, regulate worker safety or chemical safety at launch facilities. Some agencies would have taken the opportunity to consolidate their authority in this case. It just never made sense for this industry. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF), and others perform their regulatory activities at places far more dangerous than launch sites, e.g. petroleum refineries, chemical and fertilizer plants, ocean ports, etc. It would be pretty onerous and presumptuous for OCST to think it could do better, or that its risks were more complex than those.

Feature of the Launch License: Operator’s License

From the very start, everyone was thinking in terms of a launch license. It began with the “export launch license” that was issued by the Department of State. Current thinking at the time was that companies conducted individual launches on separate missions. This was a carryover from contemporary NASA and USAF practice. It just seemed logical to everyone that licenses would be issued on a mission by mission basis.

The problem with that thinking was that there was no transportation industry in which government agencies routinely regulated their industry on a trip by trip basis. It didn’t make sense. For OCST, there were some interim challenges to treating this industry like other transportation industries.

From the beginning, the goal was to get to a state where commercial launches were treated like any other transportation industry. For OCST, there were some interim challenges to reaching this goal. First, the concept that the companies were operators was non-existent. OCST was limited by the concepts of the day. If NASA and the USAF addressed launches as individual activities, we were going to have to also, at least temporarily.

Second, OCST needed the individual licenses as a test bed. We knew there were variations between and amongst launches. We needed to review and approve enough licenses that we were confident we knew the critical long-term components to include in an operator’s license and how to craft the “conditions” of the license.

Finally, we needed the industry to want the product. Until they started asking that we look at them as operators, they weren’t looking beyond the next “mission”. They needed to see themselves as permanent players in space who were prepared to take on all the long-term responsibilities and were willing to claim their status as space transportation providers.